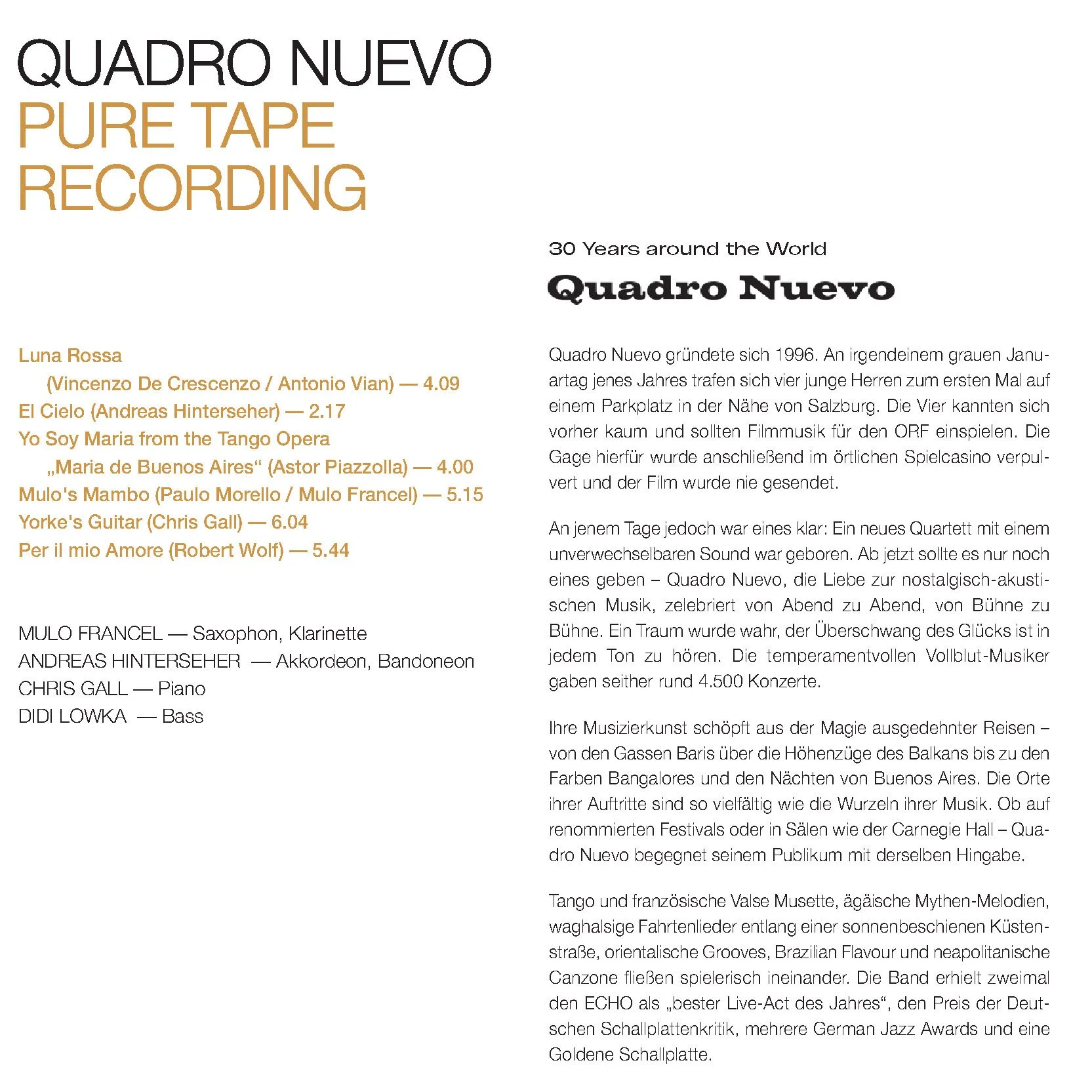

QUADRO NUEVO - PURE TAPE RECORDING

30 Years around the World

Publisher: Pure Tape Recording / Sieveking Sound

Playing time: 27 min

Specifications: half track ¼“, stereo, SM 900, 510 nWb/m, CCIR, 38 cm/s

Reel(s): 1 high quality metal reel, with sticker

Packaging: 1 standard cardboard box, with stickers, 1 cardboard slipcase

Inserts: 1 booklet with 4 pages

Order: https://www.sieveking-sound.de/musik.html

Direct Order: info@dominiqueklatte.de

Author: Claus Müller

The group Quadro Nuevo was founded in 1996. The quartet focuses on concerts and tours worldwide. Their encounters with different musical cultures have a major influence on their compositions. In this way, they build bridges between musical traditions. I interviewed Mulo Francel, the band's leader, to discuss all the exciting questions surrounding Quadro Nuevo's music and Dominique Klatte's analog recordings for the Pure Tape Recording label.

Claus: Quadro Nuevo was founded in 1996. Where and how did you meet and how did you become a band?

Mulo: I was in a school band with bassist D. D. Lowka in the small town of Rosenheim in Upper Bavaria. We got to know the other musicians and formed a quartet. That was almost 30 years ago. We started recording film music for Austrian radio. As a band, we got together for our first recordings: Robert Wolf on guitar, Heinz-Ludger Jeromin on accordion, D. D. Lowka on bass, and me, Mulo Francel, on saxophone and clarinet. We performed at many concerts. Everything worked perfectly from the start, so we stayed together. We recorded our first album, Luna Rossa, in 1996, and it was released in 1998. It won the German Jazz Award. That motivated us to keep going.

Claus: Do the band members have classical musical education? Feel free to say something about each musician from the current production.

Mulo: I was self-taught at the beginning and came to jazz through my father's record collection, who died prematurely. I started improvising on the guitar and then on the saxophone, which I bought when I was 16. It was jazz from the 1950s and 1960s, like Miles Davis, Wes Montgomery, and Stan Getz. I really wanted to be part of it. In our rural region, there were no role models, no teachers, and so on. It was a rocky road, but in the end, I studied jazz at the conservatory in Linz (Austria). It was one of the first jazz programs available at the time. D. D. Lowka, the bassist, followed me. The pianist Chris Gall has classical piano education and then went to Berkeley (USA) to study jazz. The accordionist Andreas Hinterseher studied accordion at the Richard Strauss Conservatory in Munich.

Claus: I can identify tango as a central component of your music. Added to this are elements from jazz, world music such as flamenco or Balkan swing, something Mediterranean, French influences, and improvisations. How do you bridge the gap between these musical traditions, and how do you bring the rhythms, melodies, and styles together?

Mulo: It is not our aim to play tango, French musette, waltzes, or other styles authentically. Our approach to music has developed into a style of its own. For example, ten years ago we spent a month in Buenos Aires, Argentina, watching how the musicians there play. We thought we would have to orient ourselves towards the Argentinians, but then we realized that there are many ways of playing tango there. There is no one right or wrong way to play. We played with other musicians and showed them our style of tango. They said that was a valid way to play. In this respect, our main aim is to play in an original way, to enjoy ourselves and to reach our audience. That is more important to us than authenticity. If a Brazilian heard us play a Brazilian piece, they might say: We play bossa nova differently in Brazil. We musicians enjoy peppering the pieces with improvisations or using the instruments in ways that are not used in the original. We also use rare instruments such as a Neapolitan mandolin, the vibrandoneon (an accordion you blow into) or the contrabass clarinet.

Our former guitarist Robert Wolf, who was with us from the beginning, died in 2008 after a serious traffic accident. Since then, we have been playing with various musicians in his place. Sometimes it's pianist Chris Gall, vibraphone player Tim Collins, or young guitarist Philipp Schiepek. We enjoy playing with different musicians. They bring in new trends that we incorporate and experiment with. Much of what we do has come about through trial and error, according to the motto: Let's give it a try. If an idea doesn't work, I must sit down at the piano again to rearrange the piece.

We observe the scene: how do Giora Feidman (clarinetist), Richard Galliano (accordionist), Paolo Fresu (trumpeter), or world musicians play? We don't have a role model. We want to find our own way. That's a disadvantage because you must think and experiment a lot, but it's also a big advantage because we don't have to be an ideal copy. Let me give you an example: When playing the piece Yo Soy Maria from Astor Piazzolla's tango opera Maria de Buenos Aires, which we had never recorded before, there was a lot of thought involved: What suits the female lead character Maria de Buenos Aires? She seems like a surreal figure who, I believe, is the personification of tango for Astor Piazzolla, the incarnation of tango. She was a simple girl from the gutter, for him a mother, whore, and heroine all at once. Our interpretation, which is somewhat wild, fits this. We keep changing the key and the timbre. We are guided by the style, but we also bring in colors that interest us, such as modern jazz harmonies. By modern, I mean jazz from the late 1960s onwards.

Music is often difficult to put into words. You can ask questions and give answers, but that doesn't always get to the heart of the music. You can outline it. How do you describe the colors in a picture, what is red, what is blue?

Claus: When do you come up with your ideas and songs?

Mulo: Our travels inspire our music; they give us access to new music that we would never find, even if we searched the internet. Last spring, for example, we were in India. There we attended classical Indian concerts, which were very strange to our ears. They lasted three to four hours. After two hours, you think: Okay, it could be over now. But then, when you're sitting in the fourth concert, you're used to it. I found it very exciting. I don't know yet exactly what we'll take from it into our music. In general, I would say that traveling inspires our songs and our way of writing music.

Claus: I’d like to move on to the recording for Pure Tape Recording. Was it a new situation for the band to record the tracks live and in one take on tape?

Mulo: Yes, because you can't change anything afterwards. There's no possibility of saying, “Hey, let's make the bass louder or the saxophone a little softer.” It requires a lot of trust in the sound engineer. It's nice when you can say, “Okay, we'll play the piece five times until it sounds right.” In terms of sound, we relied completely on sound engineer Dominique Klatte. We looked for a room with good acoustics. This type of recording took some getting used to because since the early 1980s we had been accustomed to working with digital signal transmission, which allows for multitrack recording. You can record everything precisely and neatly separated on individual tracks and then adjust it later. This time, we stayed completely on the analog level, just as they did in the 1940s and 1950s before multitrack technology came along. That was a new challenge. The signals blur more into each other, the room always resonates, you can't mute it. This recording technique has its own rules, and that's fine. It's for people who like to hear it that way. I think the recording turned out excellent for that.

Claus: Will you continue with this type of analog recording in the future?

Mulo: We won't always do that because we also want to cater to people who stream, listen to CDs, or listen to vinyl. No one in Quadro Nuevo has a tape recorder anymore. In 1989, I completed my training as a sound engineer at the School of Broadcasting Technology in Nuremberg. That's where I learned to edit audio tapes. At the time, I thought it was almost obsolete and was looking forward to CDs. Nowadays, there's something nostalgic, almost archaic, about recording music on magnetic tape and working with tape saturation. I find that exciting. I won't be listening to music on tape in my private life. My life is too hectic for that; I don't have enough peace and quiet. Sometimes I treat myself to a vinyl evening with friends. I could imagine doing that with a tape recorder too. I think it's good that there are enthusiasts out there. We were at Dietmar Winter's house and listened to CDs versus tape. We could appreciate the warmth and directness that came across from the tape.

Claus: Is there anything else you would like to say in this interview?

Mulo: This recording was an exciting experience for us. It was a great collaboration with the sound engineer, whom you place a lot of trust in when you're not constantly listening to the recording as you would in a digital studio. We did listen occasionally, but then we said to ourselves: Let's concentrate on the music and leave it to Dominique Klatte, the sound engineer. It was a trip back to the analog age that we really enjoyed.

We're planning some big concerts next year to mark Quadro Nuevo's 30th anniversary. If we have master tape copies at our merchandise stand at the Isar Philharmonic in Munich on February 18, 2026, for example, I think that's great and I'll be very happy. I'm proud of that because not every band has that. Many musicians are making vinyl again, but an audio tape is cool.

Claus: Thank you very much for answering my questions in detail.

Conclusion

I view Mulo Francel's statement that there was no multitrack technology used in the current recording, that the signals blurred into each other and the room contributed to the sound, as positive and see it as an advantage that the audio signal did not originate from studio processing. The acoustic event is reproduced very faithfully by the tape. The live performance thus finds its way into the listening room at home. Compared to many pure studio recordings, this music is reproduced in a very organic and lively way. You are right in the middle of it and can really feel how well the quartet harmonizes. The musicians merge into a single sound body, from which the solo moments skillfully stand out. Listeners can expect six professionally and sophisticatedly played musical treats. The album reflects the artistry of a great quartet that has found its own style. Despite the relatively short total playing time of the tape, Quadro Nuevo has done an excellent job of providing a cross-section of 30 years of musical creativity, and it is highly recommended for all lovers of good music and perfect sound.

One final tip: listen to the tape using good headphones that are connected directly to the tape recorder if possible. I think you'll be just as amazed as I was at how faithfully instruments can be recorded and reproduced. It's a true art form!

Translated from German with www.DeepL.com (free version)

Music:

Sound:

The entire content and the individual elements of the web page are the intellectual property of Claus Müller and are subject to copyright protection. They may not be copied or imitated in whole or in part by the user; this applies to texts, logos and image components. Any modification, duplication, distribution or reproduction of the website or parts thereof, in any form whatsoever, is not permitted without the prior written consent of Claus Müller.

Der gesamte Inhalt und die einzelnen Elemente dieser Webseite sind geistiges Eigentum von Claus Müller und unterliegen dem Schutz des Urheberrechts. Sie dürfen vom Nutzer weder kopiert noch im Ganzen oder in Teilen imitiert werden; dies gilt insbesondere für Texte, Logos und Bildbestandteile. Jegliche Veränderung, Vervielfältigung, Verbreitung oder Wiedergabe der Webseite sowie Teilen hiervon, gleich welcher Art, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Zustimmung von Claus Müller nicht zulässig.