Author: Felix Hennevogl

Helmut Walcha (1907–1991) became Günther Ramin's youngest organ student at the Leipzig Conservatory at the age of 15. From 1926 to 1929, he was Ramin's deputy at St. Thomas Church in Leipzig (Germany), where he developed into an important Bach interpreter. Later, he taught as a professor in Frankfurt am Main (Germany) and was organist at the Dreikönigskirche. The focus of his work was the “Frankfurter Bachstunden” (Frankfurt Bach Hours). These were lecture concerts that combined analysis and listening experience. Walcha achieved worldwide influence on Bach interpretation through his recordings, using historical organs.

Erich Thienhaus (1909–1968) studied physics and mathematics and then completed an artistic education in organ and instrument studies. In 1946, he was appointed lecturer in acoustics and instrument studies at the newly founded Nordwestdeutsche Musikakademie (Northwest German Music Academy) in Detmold, now the Hochschule für Musik Detmold (Detmold University of Music). As a professor there, he founded the first German musical-acoustic institute for the training of sound engineers in 1949, which is now called the Erich-Thienhaus-Institut (Erich Thienhaus Institute).

Erich Thienhaus, Helmut Walcha, and the Archiv Produktion label

After the end of World War II, many organs were destroyed or damaged. Erich Thienhaus therefore suggested documenting the remaining historical organs for posterity. In collaboration with musicologist Fred Hamel, a separate label called Archiv Produktion was launched at Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft (DGG). This soon developed into a vision of documenting early music on vinyl, which ultimately covered twelve areas of research ranging from Gregorian chant to early classical music. Each record came with an archive card containing information. The recording medium was audio tape.

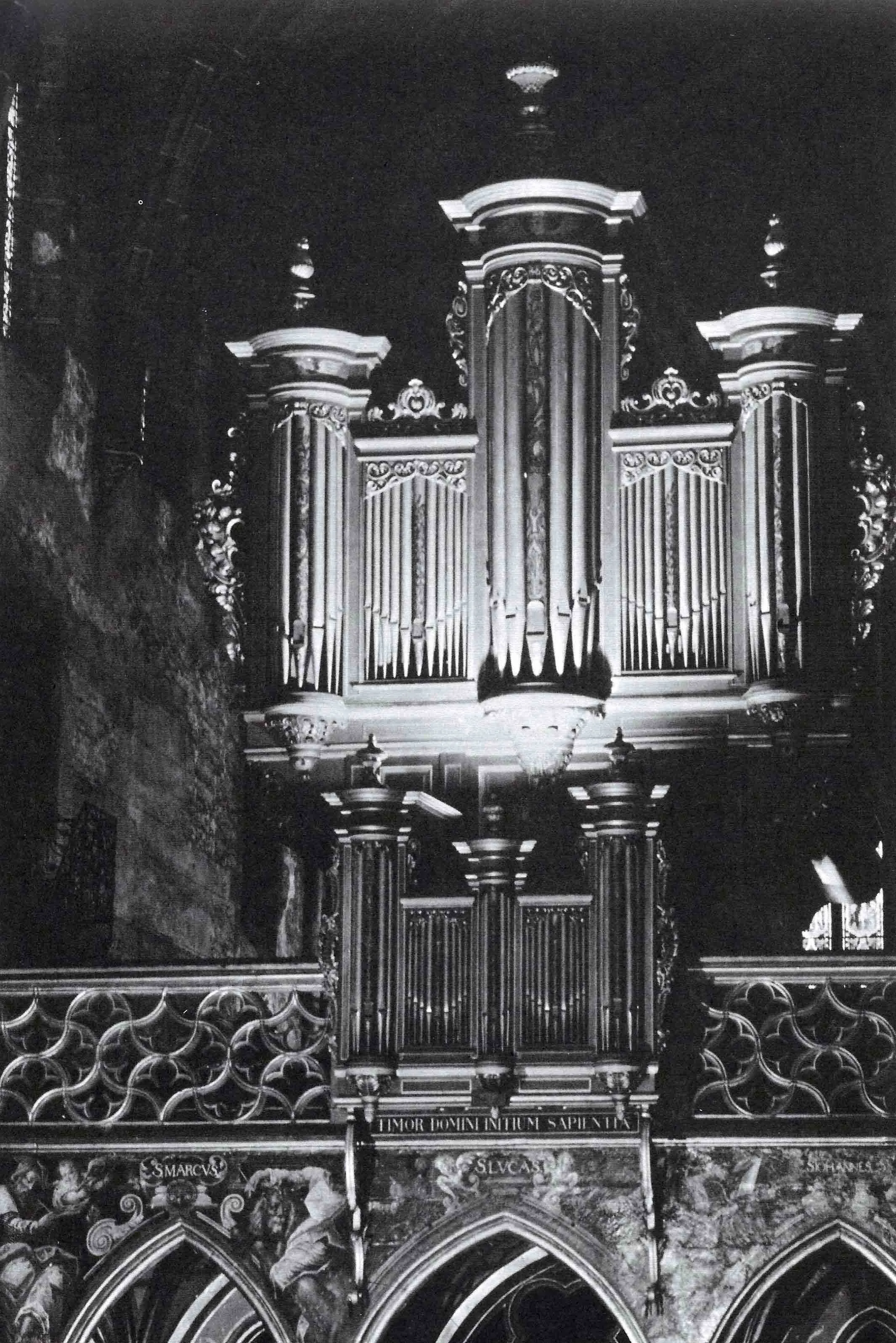

Walcha and Thienhaus had already produced an internationally acclaimed complete recording of Bach's organ works in mono between 1947 and 1952. The first recording from 1947, Toccata and Fugue in D minor, was released on shellac and marked the start of the newly founded Archiv Produktion series. Technology developed rapidly, and DGG was also challenged by the competition to introduce stereophony. They had recorded most of the mono cycle on an Arp Schnitger organ from 1680 in Cappel, northern Germany. However, this instrument proved inadequate for new stereo recordings with increased spatial content, as the limited reverberation time in this room, which covers only 1,807 m², did not allow the sound to develop sufficiently. In addition, there was excessive amplification in the low-frequency range. The organ was originally designed for the large Johanniskirche in Hamburg and was not installed in the much smaller church in Cappel until 1816. Another Arp Schnitger organ, located in St. Laurenskerk in Alkmaar, Netherlands, proved to be ideal for the upcoming project. In the large, wonderfully sounding Gothic church interior, it is still considered one of the best organs for Baroque music today.

It was September 1956 when Walcha and Thienhaus gathered at St. Laurenskerk to herald a new era for DGG: they began recording Johann Sebastian Bach's organ works in stereo for the first time. They covered research area IX (Johann Sebastian Bach), series F (works for organ). After Thienhaus's untimely death, Walcha completed the stereo cycle recordings in 1971 with Gerd Ploebsch and Hansjoachim Reiser.

Viewed as a whole, the Archiv Produktion at Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft created an impressive historical record in terms of technology and interpretation – from shellac to mono records to hi-fi stereo LPs – and now, back to its roots, as a master tape copy.

The organ works of Bach and their interpreter Helmut Walcha

On September 14, 1956, Helmut Walcha recorded Bach's The Art of Fugue. The recording is considered the earliest (published) stereo recording by Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft. From September 16 to 19, he recorded the Prelude and Fugue in C major, the Toccata and Fugue in D minor, and the two Trio Sonatas for Organ in E-flat major and G major. These four works were released at the end of 1958 as an Archiv Produktion on SAPM 198002.

The opening motif of the Toccata and Fugue in D minor (BWV 565) is, in terms of its recognizability, comparable only to the first four notes of Beethoven's Symphony No. 5. It is considered the most famous organ work in music history and was published after 1750 in a copy by Johannes Ringk. However, no manuscript by Bach exists. Could it be that this famous work attributed to Bach was not actually written by Bach? Bach researchers are divided in their opinions. It could be an early organ piece from Bach's Arnstadt period before 1705 or a transcription of one of his harpsichord or violin pieces. However, the more common theory is that it is the work of one of Bach's contemporaries, such as Johann P. Kellner. Stylistically, there is some evidence to support this assessment, but even computer-assisted stylistic analysis has so far failed to provide a clear result. Helmut Walcha takes the work seriously and interprets it entirely in the spirit of Bach. His registration is tasteful and avoids any romantic exuberance. He plays the fugue, which is rather untypical for Bach and not contrapuntally worked out, transparently and clearly, and the recurring toccata theme with verve and power.

The two Trio Sonatas for Organ in G major (BWV 530) and E-flat major (BWV 525) are among six works that Bach composed for his son Friedemann to practice. They are considered a touchstone for organists. Their difficulty lies in the independent musical leadership of three voices, distributed between the left hand, right hand, and pedal. Helmut Walcha's special method of learning compositions stands him in good stead here: due to a smallpox vaccination, he had been visually impaired since childhood and went blind at the age of 19. However, he did not use Braille music notation, but had the individual voices played to him, learned them by heart, and put them together to form the whole. In this way, he achieved complete independence of the voices and a thorough understanding of the works from within. A fascinating process that corresponds wonderfully with Bach's compositions.

Let us now turn to what I consider to be the most significant work in the Archiv Produktion SAPM 198002: Prelude and Fugue in C major (BWV 547). It is one of Bach's late works from his time in Leipzig after 1723 (presumably 1745). The prelude is 9/8 time and invites you to count along: 123456789123456789... The turns, colors, and harmonies that unfold over the powerful bass notes lead to great musical enjoyment. The following fugue is in five parts and showcases the entire art of fugue technique. Follow the entries of the voices! The fugue theme is heard 46 times. Look forward to the pedal entry in the low register in augmentation (1) of the theme in the last third, which leads the fugue to five voices. Fascinating chords above the low C in the bass conclude the recording. Walcha chooses a brightly lit registration that corresponds to the Baroque significance of the key of C major and avoids any pathos in the final chords, giving the piece a deeply penetrating and still impressive performance.

Regarding the work, it should be noted that despite the use of a Baroque organ, this cannot be considered an interpretation in line with today's historical performance practice. Walcha plays clearly and structurally, but with little agogic (2) and expressive phrasing. He ends the sections with clear ritardandi (3), and repetitions are not embellished with ornamentation. Nevertheless, the interpretations have aged exceptionally well and represent the noble and timeless Bach style of a great artist.

The master tape copy

Christoph Stickel is responsible for the analog processing of the original audio tapes. He is a mastering engineer and sound engineer who has been working in this field since 1992 and has been based in Vienna with his CS MASTERING STUDIO since 2016. You can find out more about his work at https://www.audiotapereview.com/202303csmastering. Stickel lectures and teaches postgraduate courses at the Erich Thienhaus Institute in Detmold and at the Musikhochschule Wien (Vienna University of Music). He is a brand ambassador for REVOX.

The sound

“A master tape copy is the perfect medium for organ recordings.” This statement by Volker Lange, founder and head of the Horch House brand at REVOX, needed to be tested. I had original records at my disposal, both in an early pressing from 1963, already RIAA equalized (the first edition still uses an older DIN characteristic curve and is not recommended), and in later remastered versions from the 1970s (see source information). The LPs alone offer astonishing sound quality. The two works, Prelude and Fugue in C major (BWV 547) and Toccata and Fugue in D minor (BWV 565), are recorded with a successful mix of direct and spatial sound, and the individual organ registers can be clearly located. The lower notes are clearly audible from the organ pipes arranged in the center. The low bass is captured in a spacious manner. The sound of the Trio Sonatas for Organ in G major (BWV 530) and E-flat major (BWV 525) differs slightly. It seems more direct, with less spatial presence. In some places, there are slight impurities in the presence range, possibly caused by the technical limitations of early recording technology (*).

In Claus Müller's listening room, I heard the master tape copy for the first time in comparison to the vinyl record. The Gothic church interior of Alkmaar appears much larger in reproduction, and the organ registers are more clearly locatable. The overall sound image seems more natural and seamless. The blowing noises of the organ pipes and the mechanical processes of the musical instrument are now integrated into the church interior. It is very impressive that this is a copy of a master tape that is around 70 years old. Of course, the master tape copy does not solve the minor technical problems with the trio sonatas, but it is now possible to distinguish reflections in the nave from impurities in the presence range. This makes the master tape copy the undisputed perfect medium for these organ recordings.

The Studio Master Copy was released by REVOX Horch House. The sturdy cardboard slipcase (deluxe box) contains two plastic archive boxes, each with a 26.5 cm metal reel, and a folder with five glossy prints. This audio tape edition leaves nothing to be desired.

Explanations:

(1) Augmentation: A process in which note values are enlarged

(2) Agogics: The study of the individual shaping of tempo in musical performance

(3) Ritardando: Gradual slowing of tempo during a piece of music

Translated from German with DeepL.com (free version)

ARCHIV

PRODUKTION

DES MUSIKHISTORISCHEN STUDIOS DER DEUTSCHEN GRAMMOPHON GESELLSCHAFT

IX. FORSCHUNGSBEREICH

Das Schaffen Johann Sebastian Bachs

SERIE F: WERKE FÜR ORGEL

Helmut Walcha an der Orgel der St. Laurenskerk in Alkmaar

Publisher: REVOX Horch House

Playing time: 46 min

Specifications: half track ¼", stereo, RTM SM900, CCIR, 510 nWb/m, 38 cm/s

Reel(s): 2 precision metal reels, printed, with stickers

Packaging: 2 plastic archive boxes, with stickers, 1 cardboard slipcase

Inserts: 1 insert folder with 2 insert sheets and 3 photo prints

Homepage: https://www.horchhouse.com/

Music:

Sound: with slight downgrading for two tracks, see text (*):

Interpretation:

The entire content and the individual elements of the web page are the intellectual property of Claus Müller and are subject to copyright protection. The text of this review is the intellectual property of Felix Hennevogl. The contents may not be copied or imitated in whole or in part by the user; this applies to texts, logos and image components. Any modification, duplication, distribution or reproduction of the website or parts thereof, in any form whatsoever, is not permitted without the prior written consent of Claus Müller or Felix Hennevogl (for the text of this review).

Der gesamte Inhalt und die einzelnen Elemente dieser Webseite sind geistiges Eigentum von Claus Müller und unterliegen dem Schutz des Urheberrechts. Der Text dieser Rezension ist geistiges Eigentum von Felix Hennevogl. Die Inhalte dürfen vom Nutzer weder kopiert noch im Ganzen oder in Teilen imitiert werden; dies gilt insbesondere für Texte, Logos und Bildbestandteile. Jegliche Veränderung, Vervielfältigung, Verbreitung oder Wiedergabe der Webseite sowie Teilen hiervon, gleich welcher Art, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Zustimmung von Claus Müller oder Felix Hennevogl (für den Text dieser Rezension) nicht zulässig.